The following interview was conducted in hyperspace in hyperdrive in order to reduce hyperbole and its accompanying hypertension.

Q. I understand you had a few days of strong winds. What should one do when encountering such winds?

A. That depends. One can continue biking, slowly but surely (coincidently building up strength and stamina) and perhaps alternating with walking the bike. Or, one can stop, relax, take a nap or enjoy the scenery and wait for the winds to diminish.

A. That depends. One can continue biking, slowly but surely (coincidently building up strength and stamina) and perhaps alternating with walking the bike. Or, one can stop, relax, take a nap or enjoy the scenery and wait for the winds to diminish.

Q. You had one flat on each of your bicycle trips to San Diego. How did you manage that?

A. The use of "tire guards" may have helped. These are plastic strips that one places between the tube and the inside of the tire. They seem to work best against penetration from blunt objects as opposed to thin steel wire--such as the type of wire embedded in truck tires and which scatters about on interstate highway shoulders when the tire tread fails. Bits of these wires seemed to have been the cause of the first five of six flats experienced during the

2015 trip--each of the first flats occurred on an interstate highway. It is possible that, when repairing the first of the five flats, additional pieces of these wires, which may have embedded themselves in the bicycle tire, were overlooked, and ultimately caused the subsequent flats. The one flat experienced during the

2001 trip was caused by what appeared to be a packing staple.

A. The use of "tire guards" may have helped. These are plastic strips that one places between the tube and the inside of the tire. They seem to work best against penetration from blunt objects as opposed to thin steel wire--such as the type of wire embedded in truck tires and which scatters about on interstate highway shoulders when the tire tread fails. Bits of these wires seemed to have been the cause of the first five of six flats experienced during the

2015 trip--each of the first flats occurred on an interstate highway. It is possible that, when repairing the first of the five flats, additional pieces of these wires, which may have embedded themselves in the bicycle tire, were overlooked, and ultimately caused the subsequent flats. The one flat experienced during the

2001 trip was caused by what appeared to be a packing staple.

Q. Would you recommend taking an extra bicycle tire on lengthy cross country trips?

A. Probably not. If one buys good quality tires to begin with, they should last the entire trip--at least a one-way trip from Boston to San Diego. During a much longer trip--such as the

2015 round trip--having to buy one or more new tires is more likely but not necessarily inevitable. Occasionally checking the tires during one’s trip should provide sufficient notice of the need to replace a tire at some conveniently manageable point along one's route. In case of catastrophic failure of a tire (as happened during the

2015 trip when a three-inch screw abraded and embedded itself in the rear tire, near the Kansas/Missouri border), detouring to the nearest town likely to have an appropriate replacement tire may be advisable, rather than waiting until arriving at a more distant town located on one’s itinerary. Strategically rotating the tires between the front and rear wheels during a lengthy trip will serve to increase the life of the tires, as tires on the drive wheel wear faster than those on the front wheel.

A. Probably not. If one buys good quality tires to begin with, they should last the entire trip--at least a one-way trip from Boston to San Diego. During a much longer trip--such as the

2015 round trip--having to buy one or more new tires is more likely but not necessarily inevitable. Occasionally checking the tires during one’s trip should provide sufficient notice of the need to replace a tire at some conveniently manageable point along one's route. In case of catastrophic failure of a tire (as happened during the

2015 trip when a three-inch screw abraded and embedded itself in the rear tire, near the Kansas/Missouri border), detouring to the nearest town likely to have an appropriate replacement tire may be advisable, rather than waiting until arriving at a more distant town located on one’s itinerary. Strategically rotating the tires between the front and rear wheels during a lengthy trip will serve to increase the life of the tires, as tires on the drive wheel wear faster than those on the front wheel.

Q. Is there any notable difference between Presta and Schrader valve inner tubes?

A. Other than obvious differences in physical nomenclature, Presta valve tubes seem to hold the desired air pressure for a few days more than do Schrader valve tubes. During both the

2001 and

2004 trips, when only Schrader valve tubes were used, the tubes seemed to require pumping at least twice a week. During the

2015 trip, when Presta valve tubes were used, pumping seemed to be needed no more than once a week in order to maintain the desired air pressure. When using Presta valve tubes, consider carrying a valve adapter, which allows use of foot pumps designed solely for Schrader valves. Because most commercially readily available compact foot pumps are designed for Schrader valves only, finding a store which carries such a pump--should the need for a replacement arise during one's trip--is easier than finding a store that carries Presta valve compatible pumps.

A. Other than obvious differences in physical nomenclature, Presta valve tubes seem to hold the desired air pressure for a few days more than do Schrader valve tubes. During both the

2001 and

2004 trips, when only Schrader valve tubes were used, the tubes seemed to require pumping at least twice a week. During the

2015 trip, when Presta valve tubes were used, pumping seemed to be needed no more than once a week in order to maintain the desired air pressure. When using Presta valve tubes, consider carrying a valve adapter, which allows use of foot pumps designed solely for Schrader valves. Because most commercially readily available compact foot pumps are designed for Schrader valves only, finding a store which carries such a pump--should the need for a replacement arise during one's trip--is easier than finding a store that carries Presta valve compatible pumps.

Q. Did you carry a bicycle pump?

A. Yes. A sturdy compact foot pump works nicely, and requires only a fraction of the effort required by a hand pump. Keep tire pressure at maximum recommended to ensure a fast and efficient ride throughout the day.

A. Yes. A sturdy compact foot pump works nicely, and requires only a fraction of the effort required by a hand pump. Keep tire pressure at maximum recommended to ensure a fast and efficient ride throughout the day.

Q. Were mosquitoes a problem during your trips?

A. Mosquitos were occasionally a nuisance at night during the

2001 trip, when only a tarp was used as a lean-to (resulting in three sides open to the world) for protection against rain. Having learned this lesson, an old voile curtain was used during the subsequent trips in order to enclose the open areas around the tarp, thereby ending or limiting mosquito contact.

A. Mosquitos were occasionally a nuisance at night during the

2001 trip, when only a tarp was used as a lean-to (resulting in three sides open to the world) for protection against rain. Having learned this lesson, an old voile curtain was used during the subsequent trips in order to enclose the open areas around the tarp, thereby ending or limiting mosquito contact.

Q. So, you didn't use a tent. Would you recommend a tarp over a tent?

A. This is a matter of personal preference. Tents are nice, but relatively expensive for just the occasional bicycle cross-country trip, in addition to being relatively time consuming to erect and dismantle. An appropriately sized tarp is inexpensive, is quickly folded or unfolded as needed, serves as a cushion for sleeping when not used as a lean-to, and makes a nice gift to someone in need at the end of the trip.

A. This is a matter of personal preference. Tents are nice, but relatively expensive for just the occasional bicycle cross-country trip, in addition to being relatively time consuming to erect and dismantle. An appropriately sized tarp is inexpensive, is quickly folded or unfolded as needed, serves as a cushion for sleeping when not used as a lean-to, and makes a nice gift to someone in need at the end of the trip.

Q. But what about rain, isn't a tent more protective?

A. Perhaps, but one quickly learns how to adjust and position a tarp in relation to the rain stream and the immediate landscape in order to reduce or eliminate the rain’s intrusion. Moreover, in the event of a sudden rain squall while bicycling, one can turn into a neighboring field, woods, driveway, or practically anywhere, quickly unfold the tarp and cover both bicycle and rider.

A. Perhaps, but one quickly learns how to adjust and position a tarp in relation to the rain stream and the immediate landscape in order to reduce or eliminate the rain’s intrusion. Moreover, in the event of a sudden rain squall while bicycling, one can turn into a neighboring field, woods, driveway, or practically anywhere, quickly unfold the tarp and cover both bicycle and rider.

Q. Did you stay in hotels during your trips?

A. Hotel stays were a regular and welcomed part of the trips, providing a relaxed opportunity to clean bicycle, body and laundry. Hotel stays during the first three trips were limited to one day about every seven to ten days. During the

2015 trip, the advantage of staying two consecutive days per hotel stop was discovered and became the norm.

A. Hotel stays were a regular and welcomed part of the trips, providing a relaxed opportunity to clean bicycle, body and laundry. Hotel stays during the first three trips were limited to one day about every seven to ten days. During the

2015 trip, the advantage of staying two consecutive days per hotel stop was discovered and became the norm.

Q. Where did you sleep when not in a hotel?

A. Sleeping outdoors had the benefit of permitting bicycling for as long as there was some modicum of daylight and sufficient physical energy or mental desire to continue. This allowed for travelling considerably greater distances on a daily basis than would have been the case if hotel stays were a daily part of the trip. Sleeping sites chosen depended largely on the immediate surroundings (with preference given to spots offering some concealment from traffic) including, for example, several yards into a nearby forest, field, or desert; behind shopping centers or box stores; behind a pile of dirt or at the bottom of a deep ditch along the road; in town or city parks, or at rest areas along highways; in an abandoned farm, or in a new house under construction; along a bike or hiking trail; behind large round hay bales, or in a copse of trees located in town or in the countryside.

A. Sleeping outdoors had the benefit of permitting bicycling for as long as there was some modicum of daylight and sufficient physical energy or mental desire to continue. This allowed for travelling considerably greater distances on a daily basis than would have been the case if hotel stays were a daily part of the trip. Sleeping sites chosen depended largely on the immediate surroundings (with preference given to spots offering some concealment from traffic) including, for example, several yards into a nearby forest, field, or desert; behind shopping centers or box stores; behind a pile of dirt or at the bottom of a deep ditch along the road; in town or city parks, or at rest areas along highways; in an abandoned farm, or in a new house under construction; along a bike or hiking trail; behind large round hay bales, or in a copse of trees located in town or in the countryside.

Q. Did you carry cooking gear or supplies?

A. No. A small quantity of nonperishable food was kept on hand throughout the trip for an occasional snack or as emergency sustenance pending arrival at a restaurant or store. During the first half of the

2001 trip all eating was limited to store bought food--lunchmeat, bread, cheese, fruit, etc.--until Starkville, Mississippi, when the advantage of all-you-can-eat buffets was discovered. Thereafter, and including each of the three subsequent trips, most eating was in restaurants, with preference given to buffets.

A. No. A small quantity of nonperishable food was kept on hand throughout the trip for an occasional snack or as emergency sustenance pending arrival at a restaurant or store. During the first half of the

2001 trip all eating was limited to store bought food--lunchmeat, bread, cheese, fruit, etc.--until Starkville, Mississippi, when the advantage of all-you-can-eat buffets was discovered. Thereafter, and including each of the three subsequent trips, most eating was in restaurants, with preference given to buffets.

Q. Were dogs a problem on your trips?

A. There were numerous times when dogs rushed to make their presence known, seemingly enjoying the opportunity to frolic, banter, and share a short dash in the countryside with a benign and unique moving object, their tails wagging and muzzles ajar in complacent smiles. Loudest in their barks were usually the smaller dogs, intending, seemingly, to ensure their notice. Be that as it may, it is probably best for the sake of both dog and rider to ignore the dog’s presence. The greatest threat is not that a dog will attack; to the contrary, the greatest threat is that of a collision with the dog or a passing vehicle. Be calm and confident. Avoid openly acknowledging the dog. Pedal smoothly; if possible, gradually increase speed in an effort to out-distance or tire the dog. To avoid colliding with dogs focus on the road. If traffic allows, ride towards the center of the road; dogs generally will avoid following, confining themselves to their perceived established territory. Sometimes dogs work in groups. While encounters with a pack of two or more dogs may initially provoke anxiety in one's mind, the general rules delineated above apply equally. The biggest difference between encounters with a single dog and a pack is that the latter will likely be more interesting and memorable, perhaps even comical.

A. There were numerous times when dogs rushed to make their presence known, seemingly enjoying the opportunity to frolic, banter, and share a short dash in the countryside with a benign and unique moving object, their tails wagging and muzzles ajar in complacent smiles. Loudest in their barks were usually the smaller dogs, intending, seemingly, to ensure their notice. Be that as it may, it is probably best for the sake of both dog and rider to ignore the dog’s presence. The greatest threat is not that a dog will attack; to the contrary, the greatest threat is that of a collision with the dog or a passing vehicle. Be calm and confident. Avoid openly acknowledging the dog. Pedal smoothly; if possible, gradually increase speed in an effort to out-distance or tire the dog. To avoid colliding with dogs focus on the road. If traffic allows, ride towards the center of the road; dogs generally will avoid following, confining themselves to their perceived established territory. Sometimes dogs work in groups. While encounters with a pack of two or more dogs may initially provoke anxiety in one's mind, the general rules delineated above apply equally. The biggest difference between encounters with a single dog and a pack is that the latter will likely be more interesting and memorable, perhaps even comical.

Q. Did you have to physically or mentally prepare for such long rides, and what did you most enjoy on your trips?

A. How one prepares mentally or physically for cross-country bicycling is unique to each individual. For all four trips the only conscious preparation was logistical (i.e. mapping, scheduling, provisioning, and bicycle maintenance). Mentally, there was simply the desire for an adventure, to see and experience the open air and rawness of the land and to escape the sheltered ennui of a quotidian invariability and materialistic comfort. No preparation was undertaken to physically prepare the body as the body announced itself subservient to the mind. Generally, no physical preparation is necessary if one bicycles for enjoyment rather than competition. Almost anyone can bicycle long distances, given the time, desire and resources. Essential in enjoying long distance trips is to adjust one’s riding style and speed according to one’s physical ability--which ability will improve as the trip progresses. Pleasure in such trips is to be found wherever one wishes: in the adventure, the independence and freedom, the relaxation, the 30 plus miles per hour downhill rides, the welcoming sleep under the stars, the surmounting of difficulties, the natural experience, the sightseeing, the completion of the trip itself and, ultimately, the memories--all of which, singularly or in any combination, enlighten the mind, calm the emotions and imbue one with confidence, zeal, compassion and an appreciation of life and its evanescence.

A. How one prepares mentally or physically for cross-country bicycling is unique to each individual. For all four trips the only conscious preparation was logistical (i.e. mapping, scheduling, provisioning, and bicycle maintenance). Mentally, there was simply the desire for an adventure, to see and experience the open air and rawness of the land and to escape the sheltered ennui of a quotidian invariability and materialistic comfort. No preparation was undertaken to physically prepare the body as the body announced itself subservient to the mind. Generally, no physical preparation is necessary if one bicycles for enjoyment rather than competition. Almost anyone can bicycle long distances, given the time, desire and resources. Essential in enjoying long distance trips is to adjust one’s riding style and speed according to one’s physical ability--which ability will improve as the trip progresses. Pleasure in such trips is to be found wherever one wishes: in the adventure, the independence and freedom, the relaxation, the 30 plus miles per hour downhill rides, the welcoming sleep under the stars, the surmounting of difficulties, the natural experience, the sightseeing, the completion of the trip itself and, ultimately, the memories--all of which, singularly or in any combination, enlighten the mind, calm the emotions and imbue one with confidence, zeal, compassion and an appreciation of life and its evanescence.

Q. How much did it cost for each of the cross country trips?

A1. For the

2015 trip the rough total on-the-road cost was $4536.00. This includes roughly (a) $2737.00 for restaurant meals and store bought food, and miscellaneous items, (b) $1546.00 for hotels, and (c) $252.00 for bicycle parts (new chain and cassette, three new tires, and bottom bracket). The replaced chain, cassette and bottom bracket, as well as both front and rear tires, were original parts from the

2011 trip. Both the chain and cassette were replaced in Brookings, Oregon, while the bottom bracket was replaced in Louisville, Kentucky. One of the tires was replaced early out of caution rather than necessity--as it appeared that cracks were developing on the sidewall.

A1. For the

2015 trip the rough total on-the-road cost was $4536.00. This includes roughly (a) $2737.00 for restaurant meals and store bought food, and miscellaneous items, (b) $1546.00 for hotels, and (c) $252.00 for bicycle parts (new chain and cassette, three new tires, and bottom bracket). The replaced chain, cassette and bottom bracket, as well as both front and rear tires, were original parts from the

2011 trip. Both the chain and cassette were replaced in Brookings, Oregon, while the bottom bracket was replaced in Louisville, Kentucky. One of the tires was replaced early out of caution rather than necessity--as it appeared that cracks were developing on the sidewall.

A2. For the

2004 trip the rough total on-the-road cost was $1217.00. This includes roughly (a) $632.00 for restaurant meals and store bought food, (b) $275.00 for hotels, (c) $146.00 for bicycle repair and other purchased accessories or parts (the chain, crank, and rear cassette were replaced in South Dakota—all being original equipment from the

2001 trip), and (d) $164.00 for miscellaneous expenses (including $60.00 for the bus ticket in Montana, and $58.00 for United Parcel Service to ship the bicycle from San Diego back to Boston). Return from San Diego to Boston was via air, using a frequent flier miles award ticket.

A2. For the

2004 trip the rough total on-the-road cost was $1217.00. This includes roughly (a) $632.00 for restaurant meals and store bought food, (b) $275.00 for hotels, (c) $146.00 for bicycle repair and other purchased accessories or parts (the chain, crank, and rear cassette were replaced in South Dakota—all being original equipment from the

2001 trip), and (d) $164.00 for miscellaneous expenses (including $60.00 for the bus ticket in Montana, and $58.00 for United Parcel Service to ship the bicycle from San Diego back to Boston). Return from San Diego to Boston was via air, using a frequent flier miles award ticket.

A3. For the

2001 trip the rough total on-the-road cost was $1005.00. This includes roughly (a) $470.00 for restaurant meals and store bought food, (b) $290.00 for hotels, (c) $147.00 for bicycle repair and other purchased accessories or parts (a broken pedal was replaced in Mississippi, while the rear wheel was replaced in Connecticut), and (d) $98.00 for miscellaneous expenses (including $44.00 for United Parcel Service to ship the bicycle from San Diego back to Boston). Return from San Diego to Boston was via air, using a frequent flier miles award ticket.

A3. For the

2001 trip the rough total on-the-road cost was $1005.00. This includes roughly (a) $470.00 for restaurant meals and store bought food, (b) $290.00 for hotels, (c) $147.00 for bicycle repair and other purchased accessories or parts (a broken pedal was replaced in Mississippi, while the rear wheel was replaced in Connecticut), and (d) $98.00 for miscellaneous expenses (including $44.00 for United Parcel Service to ship the bicycle from San Diego back to Boston). Return from San Diego to Boston was via air, using a frequent flier miles award ticket.

Q. Is it necessary to have a lot of gears in order to bicycle across the country?

A. The more the better. Even with 27 gears there were times when more would have been beneficial. Hills and winds will force even the most robust bicyclist to shift to the lowest gear available. Inevitably, one will encounter occasions when, no matter the number of gears, walking will be the most efficient form of forward progress. The weight of supplies, long steep hills, winds, weariness towards the end of the day, road conditions, strategic decisions to conserve energy, among other factors--singularly or in any combination--will influence gear shifting and the question how many gears are enough or whether walking may be more efficacious. In the final analysis, the number of gears matters less than how motivated one is to pursue and complete a unique adventure.

A. The more the better. Even with 27 gears there were times when more would have been beneficial. Hills and winds will force even the most robust bicyclist to shift to the lowest gear available. Inevitably, one will encounter occasions when, no matter the number of gears, walking will be the most efficient form of forward progress. The weight of supplies, long steep hills, winds, weariness towards the end of the day, road conditions, strategic decisions to conserve energy, among other factors--singularly or in any combination--will influence gear shifting and the question how many gears are enough or whether walking may be more efficacious. In the final analysis, the number of gears matters less than how motivated one is to pursue and complete a unique adventure.

Q. Did you ride on any interstate highways during your trips? Is this even permitted, or safe?

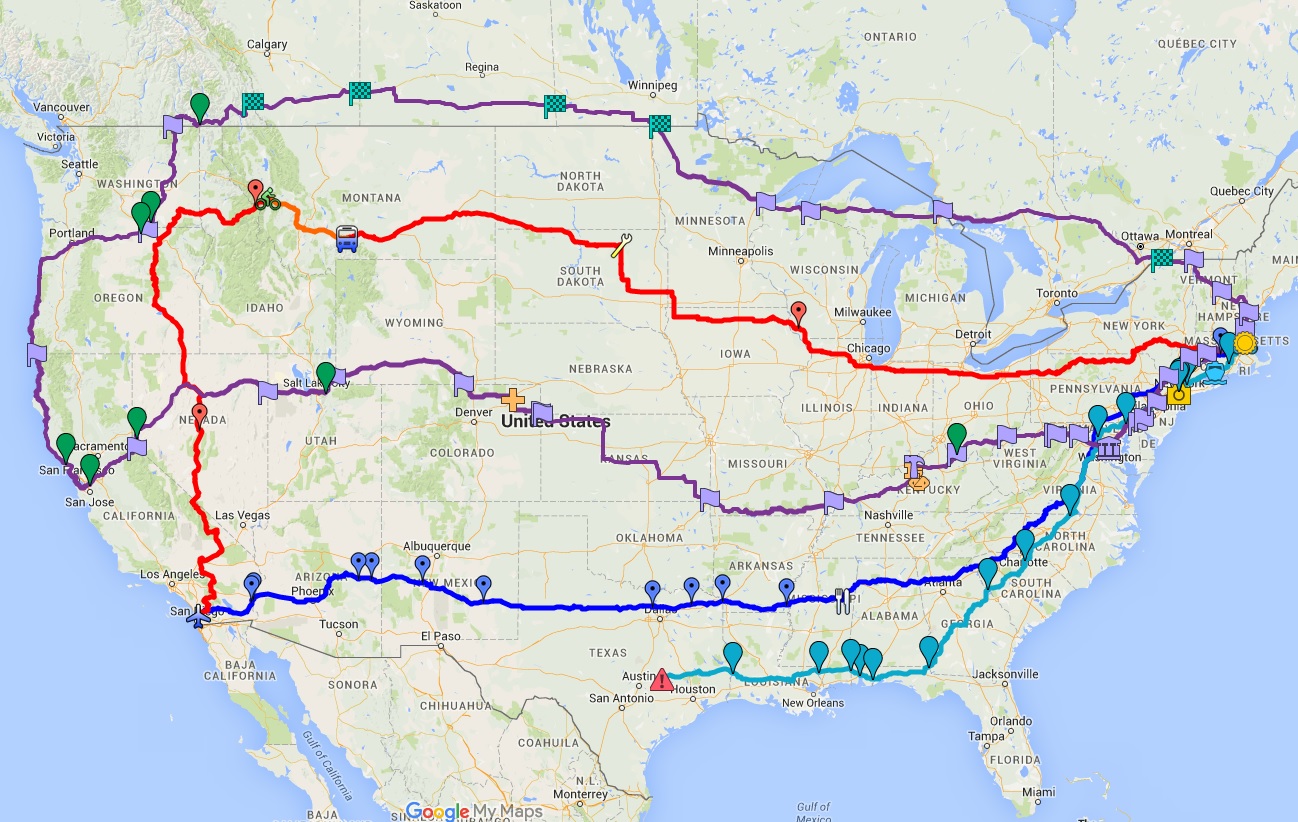

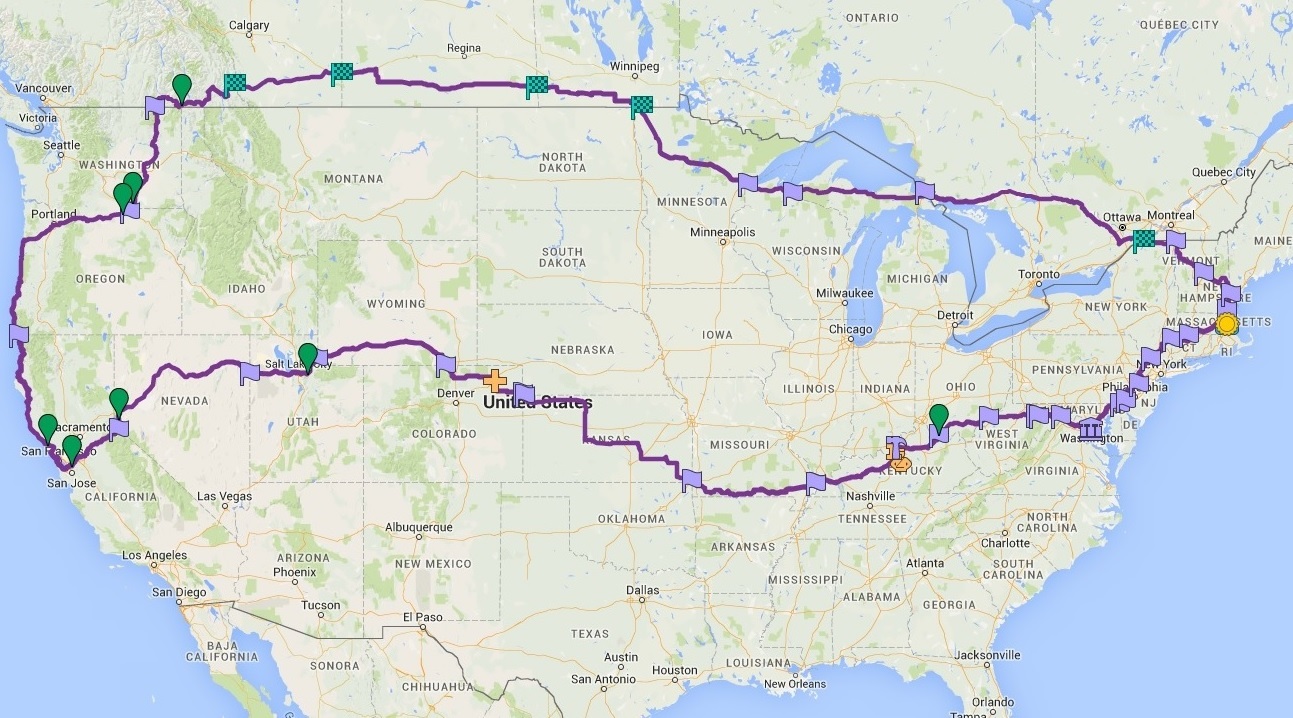

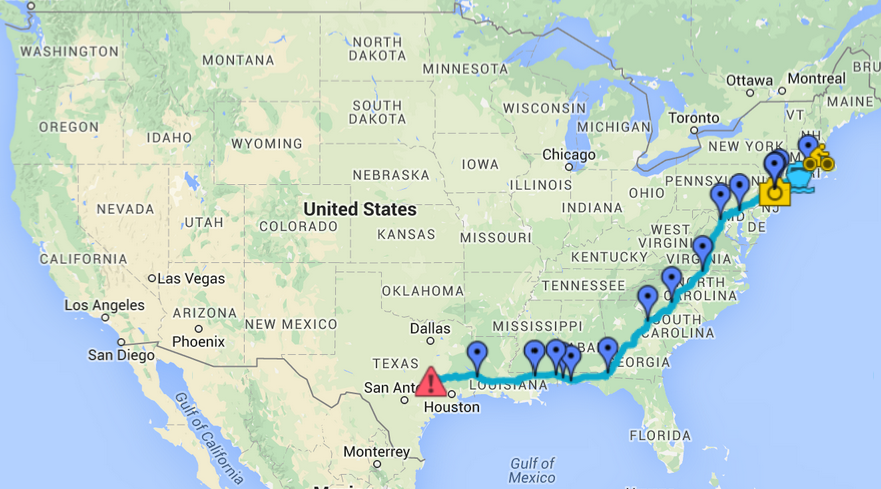

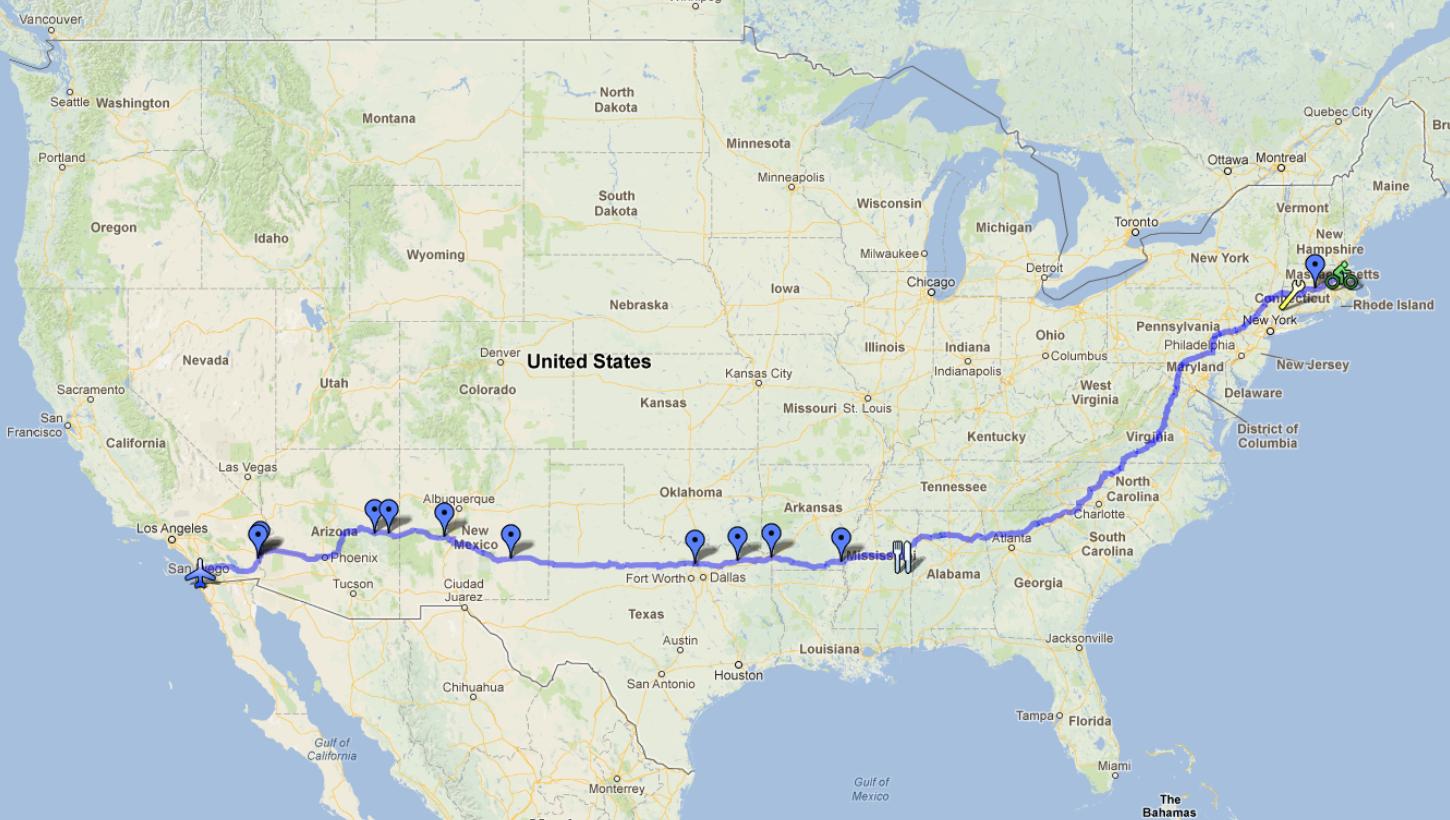

A. With the exception of the

2011 trip, all the trips included bicycling on interstate highways in one or more of the following states (see maps): Arizona, California, Colorado, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. Each state determines the extent of bicycle interstate highway access within its jurisdiction. Wyoming and Montana apparently have no restrictions, while Arizona, Nevada, and Utah prohibit bicycles from those parts of the interstate highway traversing metropolitan areas (requiring, instead, use of local roads within such areas). Oregon permits bicycles on all parts of the interstate highway--rural and metropolitan--with the proviso that bicycles exit at each exit ramp and reenter, if desired, at any following entry ramp. California’s rules are considerably more restrictive, prohibiting bicycling on those parts of the interstate highway connecting distinctive points where alternative routes are available. Generally, bicycling on interstate highways is permitted, with varying qualifications, in most states west of the Mississippi River (Kansas, e.g. prohibits bicycle access). Whether access is prohibited is usually announced on a sign at the beginning of the entry ramp. These signs should be read carefully with the understanding that, the expression of one thing is the exclusion of the other, i.e. if bicycles are not listed, then one may presume they are permitted. Once on an interstate highway, it is also possible to encounter a sign directing bicycles to exit at the next exit (or, in the absence of such a sign, to intuitively recognize that exiting is prudent or probably required). Check with the State's highway patrol for specifics before venturing onto any interstate highway. Interstate highways uniformly have a ten-foot shoulder, which provides a physically safe and psychologically comforting buffer between traffic and the bicyclist (as long as the bicyclist follows the recommended rule to ride on the extreme right of the shoulder). Most importantly, an abundance of caution should be exercised in crossing all exit and entry ramps.

A. With the exception of the

2011 trip, all the trips included bicycling on interstate highways in one or more of the following states (see maps): Arizona, California, Colorado, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. Each state determines the extent of bicycle interstate highway access within its jurisdiction. Wyoming and Montana apparently have no restrictions, while Arizona, Nevada, and Utah prohibit bicycles from those parts of the interstate highway traversing metropolitan areas (requiring, instead, use of local roads within such areas). Oregon permits bicycles on all parts of the interstate highway--rural and metropolitan--with the proviso that bicycles exit at each exit ramp and reenter, if desired, at any following entry ramp. California’s rules are considerably more restrictive, prohibiting bicycling on those parts of the interstate highway connecting distinctive points where alternative routes are available. Generally, bicycling on interstate highways is permitted, with varying qualifications, in most states west of the Mississippi River (Kansas, e.g. prohibits bicycle access). Whether access is prohibited is usually announced on a sign at the beginning of the entry ramp. These signs should be read carefully with the understanding that, the expression of one thing is the exclusion of the other, i.e. if bicycles are not listed, then one may presume they are permitted. Once on an interstate highway, it is also possible to encounter a sign directing bicycles to exit at the next exit (or, in the absence of such a sign, to intuitively recognize that exiting is prudent or probably required). Check with the State's highway patrol for specifics before venturing onto any interstate highway. Interstate highways uniformly have a ten-foot shoulder, which provides a physically safe and psychologically comforting buffer between traffic and the bicyclist (as long as the bicyclist follows the recommended rule to ride on the extreme right of the shoulder). Most importantly, an abundance of caution should be exercised in crossing all exit and entry ramps.

Q. What type of maps did you use, and how did you decide which roads to take?

A. Regular road maps available for automobile travel work equally well for bicycling. Alternatively, one may prefer to rely on some of the numerous sources offering maps prepared specifically for bicycling across the country. When using regular road maps it helps to plot with a colored highlighter, before the trip, the entire route on each individual state map (understanding, of course, that during the trip any number of reasons may intrude which may counsel deviating from the planned route). Which routes one chooses depends on one's preferences as well as legally imposed restrictions on bicycle access. Personal choice factors to consider may include, for example, the desire to go through certain states or locations, visiting friends, avoiding major cities or mountain ranges, sightseeing, or a route's degree of difficulty.

A. Regular road maps available for automobile travel work equally well for bicycling. Alternatively, one may prefer to rely on some of the numerous sources offering maps prepared specifically for bicycling across the country. When using regular road maps it helps to plot with a colored highlighter, before the trip, the entire route on each individual state map (understanding, of course, that during the trip any number of reasons may intrude which may counsel deviating from the planned route). Which routes one chooses depends on one's preferences as well as legally imposed restrictions on bicycle access. Personal choice factors to consider may include, for example, the desire to go through certain states or locations, visiting friends, avoiding major cities or mountain ranges, sightseeing, or a route's degree of difficulty.

Q. Did you have to carry a lot of water with you, or was water easy to find during your trips?

A. Obtaining water was never a problem. Tap water was readily available (at, e.g. restaurants, shopping centers, gas stations, city or state visitor centers, many but not all rest stops and, in a pinch, private homes or small businesses) and seemingly safe throughout all the trips. Of course, planning is still required for some locations. There are long stretches throughout the country that are sparsely inhabited. With this in mind, it is essential to be prepared. Two 2-liter bottles, along with three or four 17 ounce bottles, sufficed as water containers on each of the trips.

A. Obtaining water was never a problem. Tap water was readily available (at, e.g. restaurants, shopping centers, gas stations, city or state visitor centers, many but not all rest stops and, in a pinch, private homes or small businesses) and seemingly safe throughout all the trips. Of course, planning is still required for some locations. There are long stretches throughout the country that are sparsely inhabited. With this in mind, it is essential to be prepared. Two 2-liter bottles, along with three or four 17 ounce bottles, sufficed as water containers on each of the trips.

Q. Have comments, or want more answers, clarification, insights?

A. Send comments or requests to

mindbiking@yahoo.com.

A. Send comments or requests to

mindbiking@yahoo.com.